I really think the days of discussing whether or not we are at war are long gone. Hence, I wanted to take a moment to say ‘back the bus up’, but in this case I don’t think this saying quite fits. When we think about the progress occurring across New Zealand currently in the teaching of reading, I would liken the movement to a snowball effect. The momentum and impact is increasing day-by-day. Evidence-based literacy instruction (that is current, research and evidence-based and meets the needs of ALL students) is building across New Zealand and rightly so.

In response to a recent article from the University of Auckland, I wanted to take a minute, or 10, to clarify the reality of what is happening across the primary school sector right now in New Zealand. Whilst we still have a long way to go, we have come too far to be heading back down the reading war path. The war is over.

1. This article refers to there being a National Debate about how best to teach children to read

It is inaccurate that Auckland University keeps referring to the so-called reading wars. What was once a national debate has been superseded by national discussion and increasing national improvement and investigation into how the teaching of reading aligns with current research and evidence-based findings from the Science of Reading (SOR). The SOR is the largest body of research in academia and includes findings from Cognitive psychology, Neuroscience, Education and Linguistics. This international research provides a very clear direction of how ALL brains learn to read and provides a clear pathway for teachers, leaders and policy makers. Stakeholders across the sector (parents, teachers, leaders, ministry representatives and politicians) are leaning into this conversation more willingly each and every day. An example of this is demonstrated during a leaders forum discussion held in 2020 that highlights the difference the introduction of a systematic and evidence-based Structured Literacy approach is making to a group of schools across New Zealand.

2. The so-called pendulum swing continues to be a misconception

The article states, “The decline is cause for much soul-searching in education circles and sparks robust academic debate. In the media, the ‘Reading Wars’ have resurfaced. Proponents on both sides argue for the benefit of one approach, and the risk of the alternative. Typically, the ‘war’ is characterised as a face-off between the whole language and phonics.”

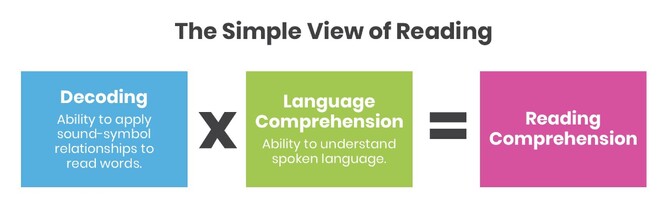

For those with robust knowledge of national and international research, this couldn’t be further from the truth. There is no pendulum swing going on. Quite the opposite. For the first time in a very long time we have an increasing body of very knowledgeable teachers who understand that systematic, evidence-based literacy instruction includes the teaching of both decoding skills and language comprehension. The Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer 1986, Hoover & Gough, 1990).

3. Irregular words within our English language

The article includes discussion regarding irregular words (these are words that don’t have completely accurate letter and sound correlation). The article states that Dr Rebecca Jesson, Associate Professor at the Faculty of Education and Social Work at the University of Auckland, does not disagree that children need to know about how letters make sounds, but with the multitude of irregular words in English, children also need to be able to think at other levels. “Working out the sound is always part of learning and part of any approach, but it isn’t the only strategy children can use. We want them to think about how it sounds as they read, but also be thinking about what the words look like, and what pictures are being created in their heads and what those mean.”

Reliance on a balanced literacy approach (or a whole language with a smattering of phonics) has led to many children in New Zealand being unable to lift words off the page that they have either seen or not seen before. You can’t gain meaning or create a picture of a word you cannot read. This makes it impossible to ‘think at other levels’. The brain does not learn to read through guessing, picture cues or reading to the end of the line and using context. Good readers don’t guess. Once our children are able to decode, then the cognitive load decreases, the focus shifts, enabling them to increase vocabulary, build language and reading comprehension and ultimately intellect. When considering instruction for novice or struggling readers, taking a whole-language or balanced approach to the teaching of reading is counter-productive and a misalignment with the findings of the Science of Reading.

I believe I speak for many knowledgeable teachers and leaders when I say we are so grateful for the influence of our knowledgeable speech language therapists across New Zealand as well as the inclusion of Linguistic research in the body of SOR findings. Dr Louisa Moats (2005) points out for us that only 4% of our language is truly irregular. Moats also teaches us about word origins and the link to meaning through the grapheme representation in How Spelling Supports Reading.

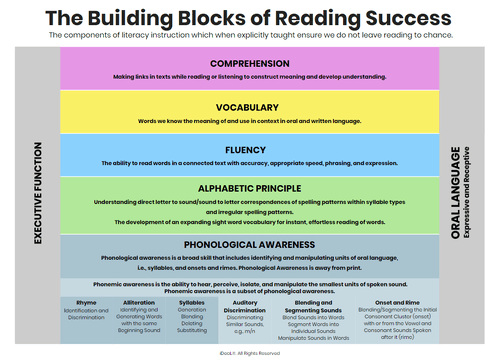

Cognitive psychologist, David Kilpatrick has been instrumental in bringing the body of research findings to our attention in a succinct way. He identifies the process our students go through to become skilled readers, assisting us with how to then best teach to develop said skills. The process is not a whole-language nor phonics approach in isolation. It does however highlight the importance of developing phonemic awareness and phonics-based knowledge early in education. The reality is as Kilpatrick (2020) states, “The best bang for your buck is tier 1 systematic phonics based instruction in year 1.” We are observing that when (junior) classroom teachers place focus on building their knowledge, assessment tools, resources, and teaching practices in those areas at the bottom of the Building Blocks of Reading Success (below), more students progress towards being literate across the curriculum and teachers are increasingly equipped to teach ALL children.

4. Reading Recovery as a dose of antibiotics

The article states, “(Reading Recovery founder Marie) Clay was clear about the role and purpose of Reading Recovery. She referred to the programme as “…like a dose of antibiotics, taken only when essential, after professional assessment, given as a full course of treatment, and varied to suit the precise condition of each individual.”

If there is a debate going on it firmly sits with why, when Reading Recovery does not naturally align with the findings of the SOR, is it still being funded in New Zealand as the main dose of intervention?

Let’s look a little closer.

All interventions in schools will be most successful when they align with mainstream classroom teaching.

- Aligning intervention normalises a learning difference, creates a more inclusive learning environment, and builds the likelihood of success.

- Implementing an evidence-based approach that meets the needs of ALL students, and applying it with consistency across all tiers will be the most effective in terms of outcomes.

The so-called dose of ‘antibiotics’ is an ambulance at the bottom of the cliff mentality - we must not WAIT to FAIL.

- In its current form Reading Recovery permits a ‘Wait to Fail’ approach. 6 is too late.

- MOE has introduced early screening and professional learning support for teachers to be teaching foundation skills from school entry through the Better Start Literacy Approach (BSLA) project. It’s a start, pardon the pun, but is it enough and does it align to the findings of the Science of Reading?

- Schools not accessing the BSLA look forward to other options of Professional Learning becoming available to support their implementation of an evidence-based approach in foundation literacy skills.

- Due to not having a national ‘dyslexia’ screening tool we are unable to identify if the majority of students referred to Reading Recovery are in fact dyslexic or if they have had dysteachia.

- Ironically, the ministry of education acknowledged dyslexia for the first time in 2007, the year Marie Clay passed.

Reading Recovery does not align with nor feature in the updated dyslexia kete cited here. Why would that be when dyslexia is the most common literacy learning difference?

At times, we must all STOP and consider what it would be like to not be able to write, to not be able to read. This is the reality for too many of our children. A literacy learning difference is not selective. In the case of dyslexia we can teach (from day one) in a way that prevents and reduces the severity of, and life-altering impact of a learning difference such as dyslexia.

In my experience, there is a direct correlation between school and literacy failure, self-esteem, self-belief and mental wellbeing. If we really want to build a nation of healthy, capable, confident, connected lifelong learners then let’s ensure we re-build an education system that teaches all the fundamental skills needed to realise this.

We look forward to policy actions such as the Literacy Strategy providing evidence-based direction that reflects both national and international findings from the Science of Reading. We look forward to the Literacy Strategy leading to KNOWING better and (respecting, but) dispelling misconceptions and approaches of old.

When we know better, we do better. As a nation we are all responsible for ensuring that our children succeed in life.

Let the quality, evidence-based systematic and informed practice snowball on. Will you wait for it to bowl you over, or will you seek the necessary knowledge and support to be prepared and equipped?

The war is well and truly over… and science won.

Carla McNeil

Carla is the Founder and Director of Learning MATTERS Ltd. Carla has been a successful school Principal, Mathematics Advisor and Classroom teacher.