At the Teaching Matters Summit in Hobart, Dr Nathaniel Swain’s keynote was an absolute standout. It was insightful, energising and full of practical wisdom about how learning and memory work.

Nathaniel began by revisiting Sir Ken Robinson’s famous claim that schools kill creativity. He explained why that argument is not supported by evidence. Rather than stifling imagination, explicit teaching lays the groundwork for it. When students master the basics through clear, well sequenced instruction, they free up space in their working memory to think critically and creatively.

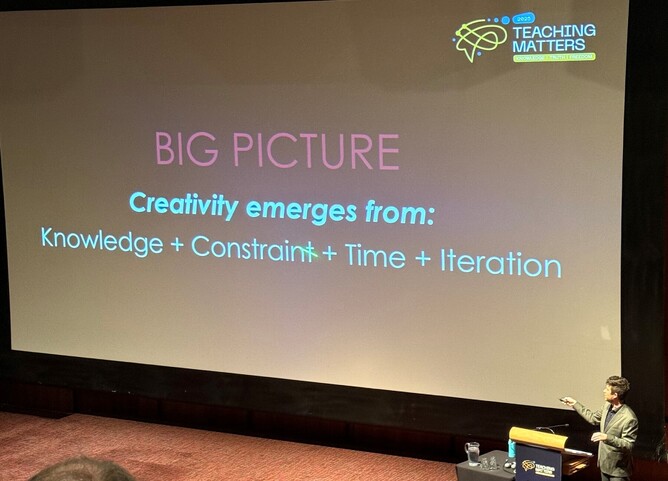

1. Creativity grows from knowledge

Creativity does not begin with a blank slate. Students cannot generate meaningful new ideas without something to build on. Knowledge is the raw material for creative thought. For instance, a student cannot write an original and insightful history essay on World War II unless they already understand the key events, timelines and concepts. Building strong knowledge foundations does not squash imagination. It fuels it.

2. Memory is the residue of thought

Nathaniel reminded us of Daniel Willingham’s famous idea that memory is the residue of thought. Students will remember what they are actively thinking about, not what we merely present. Our job is to ensure that during lessons, their attention is on the learning itself, not on distractions such as unrelated conversations, flashy slides or devices. When students are thinking hard about a concept, they are far more likely to remember it.

3. Knowledge must precede skill

We often hear that skills like collaboration, creativity or critical thinking are all that matter. Nathaniel helped us see that these skills cannot operate in a vacuum. Knowledge must come first because knowledge provides the material that skills work with. For example, a student cannot critically evaluate a scientific argument without first understanding the relevant science content. Building knowledge is not old fashioned. It is the foundation for the very skills we value most.

4. Understanding abstract ideas requires concrete examples

Students need us to connect the abstract to the familiar. Nathaniel reminded us that if we talk about a big idea without showing what it looks like in practice, students may not make the cognitive leap we are asking for. For example, if you are teaching the concept of democracy, show a concrete example such as a class vote or a well-known historical event before discussing abstract principles like representation or fairness. Bridging the known to the new makes learning stick.

5. Use explicit instruction to move knowledge from working memory to long term memory

Nathaniel explained that explicit instruction is not just the teacher talking at the start of a lesson. It is a carefully designed process that respects the limits of working memory and deliberately builds long term memory. Working memory is like a small workspace that can only hold a few pieces of new information at a time. If we overload it, students can feel confused or frustrated. Nathaniel used the swimming pool analogy: you would not throw a child into the deep end and tell them to figure out swimming on their own. Similarly, when introducing new maths or reading concepts, we must break learning into small, connected steps, link new information to what students already know, and return to important ideas repeatedly so that knowledge is stored securely in long term memory.

As students practise and consolidate, those ideas are stored in long term memory, where capacity is almost limitless. Later, when they face a new problem or creative task, they retrieve relevant knowledge from long term memory and bring it back into working memory. Because retrieval takes less effort, they can now focus on higher order thinking, problem solving or creative exploration.

This cycle of modelling, guided practice, independent practice and retrieval is what makes explicit instruction powerful. It does not stifle curiosity. It equips students with the knowledge and confidence they need to explore, inquire and innovate without being overwhelmed.

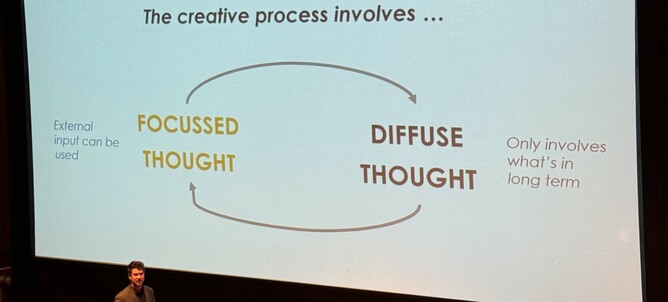

6. Allow time and space for ideas to connect

Nathaniel helped us understand why so many of our best ideas seem to appear in the shower or on a quiet walk. After focussed effort, the brain enters a phase called diffuse thinking. In this state, it draws on long term memory and makes new connections that are not possible when attention is fully engaged. For students, quiet moments without tasks, screens or noise are not wasted time. They are essential opportunities for ideas to form and creativity to spark.

7. Provide clear goals and minimise distractions

Creativity thrives within meaningful boundaries. Without clear direction, students can feel lost, and too many competing demands or screens can smother original thought. Provide simple, well-defined goals and create conditions for deep thinking. For example, instead of assigning several shallow tasks, choose one rich task that allows students to dig deeply and make meaningful progress.

8. Normalise iteration and persistence

Nathaniel shared that even Van Gogh created thousands of works before producing his masterpieces. Creativity and mastery rarely happen on the first attempt. Give students opportunities to draft, revise, seek feedback and try again. Celebrate persistence and effort as much as the polished end result.

Does explicit instruction kill creativity? As Dr Nathaniel Swain highlighted in response to Sir Ken Robinson’s famous claim, the evidence says no. When we teach core knowledge clearly and explicitly, we give students the fuel for curiosity, imagination and innovation. The real challenge is to build strong foundations, remove barriers and then give students the time and space for their ideas to bloom.

To achieve this, explicit instruction needs to be implemented in full. It is not one strategy but a set of connected practices that ensure students grasp knowledge securely, opening the door for creativity to flourish. Where are you at with this in your school?